The Ultimate Guide to Ming Dynasty Men’s Dao Robes

If we say that Ming dynasty women were most commonly seen in stylish outfits featuring ao robe (袄衫) paired with mamian skirts, then the male equivalent—the most representative everyday attire for Ming men—would undoubtedly be the Dao robe (daopao).

Ⅰ. The Popularity of the Dao Robe

Ming scholar Fan Lian wrote in Yunjian Jumu Chao, Volume 2: Notes on Customs:

“As for men’s clothing… since the reigns of the Longqing and Wanli Emperors, the Dao robe has become the standard.”

In other words, from the mid to late Ming dynasty, the Dao robe became widely worn by men from all walks of life—emperors, officials, scholars, and commoners alike.

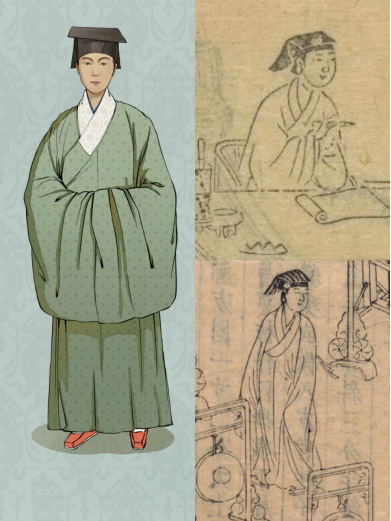

As its name suggests, the Dao robe originally had roots in Taoist religious attire. According to costume scholars Xu Xiaopan and Wang Lei, the garment evolved during the Yuan dynasty, when Taoism was strongly supported by the ruling elite. As Taoist rituals became more visible in public life, the outer Dao robe—known for its loose silhouette and flowing sleeves—caught the attention of the scholar-gentry class, who admired its elegant, refined aesthetic.

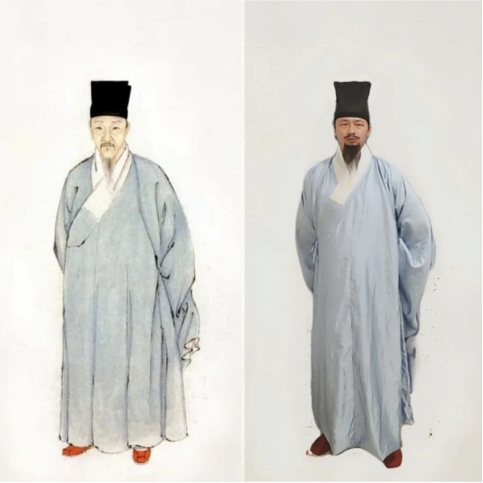

Over time, as it became more secularized, the form of the Dao robe was gradually standardized. A typical Ming-style Dao robe featured a long, straight cut from top to bottom, with a cross-collared front flap (jiaoling youren) and a collar often edged with white or plain-colored trim. It also included concealed side panels, which covered the side slits to prevent the underlayers from being seen. When wearing a Dao robe, men would typically fasten it at the waist with a silk cord, narrow cloth belt, or broader sash.

The Dao robe shown in the image above is part of the collection at the Confucius Museum. It’s dyed with natural indigo, and although the photos don’t fully capture it, the robe’s sheer fabric is woven with subtle patterns featuring cranes holding lingzhi mushrooms, as well as longevity peaches, pomegranates, and ruyi (auspicious cloud motifs).

“The design looks simple, but it’s a timeless classic. Just one glance and you can easily picture a Ming dynasty scholar wearing it,” remarked a museum expert.

When it comes to reproducing garments like this—ones that appear minimal on the surface but are rich in detail—the challenge doesn’t actually lie in replicating the intricate motifs. Instead, the real difficulty is recreating the fabric itself.

And the reason might surprise you:

“Today’s weaving machines are capable of producing ultra-fine threads. Ironically, it’s much harder to mimic the coarser, uneven hand-spun yarns used in the past.”

Ⅱ. The Fabric Matters: A Ming Dynasty Preference for Gauze

Interestingly, most of the garments from the Confucius Mansion’s historical collection are made from gauze or leno weave fabrics—a clear sign that this material was highly favored during the Ming dynasty. This discovery has inspired many modern Hanfu designers as well.

Zhong Yi, founder of Minghuatang, a Hanfu brand that specializes in Ming-style clothing, shared in an interview that after seeing the exhibition of these historical robes, he was struck by how structured and crisp the gauze fabric appeared. In contrast, although silk satin is softer to the touch, it doesn’t hold its shape as well. That insight led him to shift his entire fabric focus toward gauze for his designs.

“Another great thing about gauze is that it’s breathable,” Zhong noted. “People in ancient times often wore multiple layers underneath. A sheer outer robe made of gauze wouldn’t feel too hot, even with all the underlayers.”

Gauze Dao robes were also commonly referenced in Ming dynasty literature. In the first volume of Stories Old and New, a merchant named Chen is described as wearing

“a white gauze Dao robe and a Su-style hat with black cap.”

In Xingshi Yinyuan Zhuan, Chapter 26 describes a 18-19 young man dressed in

“a pale yellow gauze Dao robe and bright red silk shoes with pig’s snout toes.”

Ⅲ. The Color Palette of the Dao Robe

Dao robes in the Ming Dynasty came in a wide variety of colors, reflecting both personal taste and evolving aesthetics. The Ming scholar Zhu Zhiyu recorded in his work Zhu Shi Shun Shui Tan Qi that Daoist robes were commonly dyed in shades such as moon white, jade blue, sky blue, ivory, pine green, soy sauce brown, cashmere gray, and scallion white—a surprisingly rich and poetic palette.

In the early Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty, high-ranking official Lu Shusheng, then Minister of Rites, had portraits commissioned to document himself in various outfits. These portraits were compiled into a volume known as the Portrait Album of Lord Lu Wending. One particularly striking image shows the elderly Lu wearing a soft pink Dao robe.

The fact that Dao robes were not restricted to somber or neutral tones but embraced such a colorful range is a big part of why they remain a favorite among modern Hanfu enthusiasts, especially men who appreciate both the historical authenticity and the room for personal style.

Ⅳ. Styling and Structure: How Dao Robes Were Worn

The Dao robe features a straight-cut, full-length construction, with the upper and lower parts seamlessly integrated—unlike other robes that separate the jacket from the skirt. It has a straight collar with a wide, overlapping front that folds from right to left , and the inner lining often uses a similarly straight with both narrow and wide sleeves.

A signature detail is the “hidden pleat” (anbai): a fabric panel extending from the side slits at the inner and outer front lapels, which is either pleated three times or left flat, then tucked into the back seam along the spine. This helped conceal the inner garments and maintained a neat silhouette.

To complete the look, wearers often added a silken sash (丝绦) or cloth belt at the waist, not just for function but also as a pop of contrasting color to elevate the ensemble.

By the late Ming Dynasty, Dao robes began to evolve: sleeves became even wider, and the garments overall grew more voluminous and lightweight. Modern Hanfu content creators—like the blogger known as “亚力克山大” the Hanfu Enthusiast—have beautifully showcased how diverse and striking these Dao robe styles can be, highlighting both historical authenticity and artistic expression.

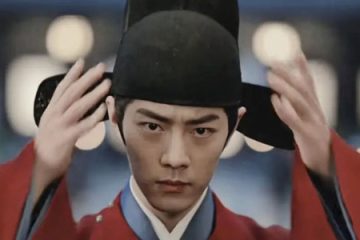

Ⅴ. How to Wear a Dao Robe

To properly wear a Dao robe, begin by aligning the inner seam (lining) with the center of your torso. Tie the inner sash snugly—but not too tight—then secure the outer sash more firmly to keep the robe in place. When worn correctly, the collar should lie flat against the body, and the front, back, and collar should all be centered. The side slits are covered by additional fabric panels, so the inner layers remain mostly hidden even during movement.

For casual wear at home, the Dao robe can be worn on its own. But when going out, it was often paired with square-toed shoes (方舃) or wooden clogs, and layered with a Zhishen (直身, a long front-opening robe), a bijia (sleeveless vest), a changyi (氅衣, formal overcoat), or a cape, to add structure and depth to the Chinese outfit.

Summary

Feeling tempted to buy a Dao robe after reading this? We wouldn’t blame you! Many Hanfu styles can feel a bit too flashy for everyday wear—but the Dao robe hits the perfect balance. It’s refined, versatile, and comfortable.

And here’s the twist: while it’s traditionally a men’s garment, plenty of women wear Dao robes too—and absolutely rock the look. Who wouldn’t be charmed by a confident glance over the shoulder in flowing robes?

Whether you’re after a scholarly elegance or laid-back cool, the Dao robe is surprisingly easy to style. Got more questions or thoughts about this timeless piece? Let’s chat in the comments below!

0 Comments