The Misunderstood “Tang Guozi”: A Cultural Heritage Mistaken for Something Else

China is not only home to the rich tradition of Hanfu clothing, but also boasts a long and flavorful culinary history. While we’ve previously explored ancient staples and traditional drinks, one area we haven’t touched on much is snacks and desserts. So today, let’s talk about Tang Guozi (唐菓子)— a traditional treat so obscure that even many Chinese people have never heard of it.

You might have seen Tang Guozi featured during the CCTV Mid-Autumn Festival Gala, where it was introduced as a delicacy dating back to the Tang Dynasty — complete with young women dressed in traditional Tang dynasty clothing presenting the treats.

But surprisingly, this sparked some confusion and controversy. Some Chinese netizens even joked, “Did the Tang Guozi company sponsor this? It’s not even an official intangible cultural heritage!” And it wasn’t just a local debate— the overseas media accounts also joined the promotion. Meanwhile, Japanese netizens were quick to comment: “Isn’t this just wagashi?”

So what’s really going on here? Let’s take a closer look and untangle the history and identity behind Tang Guozi.

Ⅰ. The Origin of the Word “Guozi”

Let’s start with the term guozi itself. The character “菓” (guǒ) originally referred to fruit, as seen in Shiji ·The Biography of Shusun Tong, where it says, “In ancient times, there was a spring ritual of tasting fruits — now cherries are ripe and ready for offering.” The Eastern Han scholar Ying Shao further explained, “Fruits from trees are called guo (菓); from vines or grasses, luo (蓏).” So at its core, guo meant “fruit.”

Over time, the term guozi evolved beyond just fruit. By the Ming dynasty, it began to refer to sweets and snacks. In the painting Summer Scene of a Traveling Vendor (《夏景货郎图》), one of the vendor’s signs reads: “Premium Guozi from Shanglin, served icy water with jade pitchers” — clearly marketing some sort of fancy refreshments or treats.

In Japan, the word kashi took on a more expansive meaning. Due to the country’s limited access to fresh fruits and challenges in preserving them, people began drying fruit, grinding it into powders, and mixing it with rice flour to create more shelf-stable confections. Over time, the concept of kashi came to include a wide range of sweets, from cakes to candies.

In fact, according to early Japanese texts like the Wamyō Ruijushō, the prototype of what we now call wagashi (traditional Japanese sweets) originated from simple rice cakes like mochi/もち — one of the earliest forms of processed food in Japan.

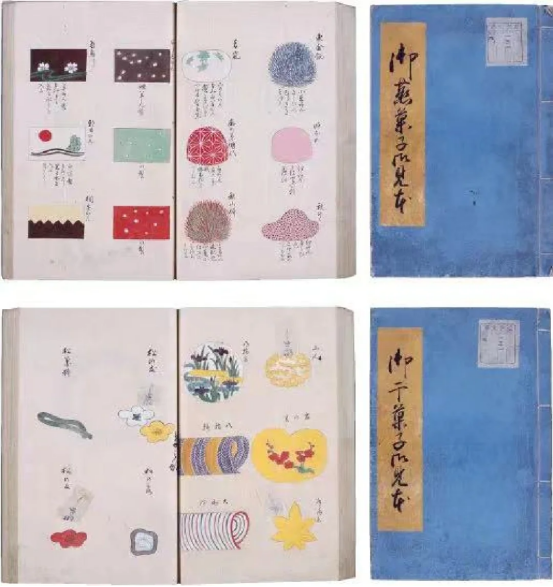

Ⅱ. Types of Wagashi (Traditional Japanese Sweets)

Wagashi comes in many forms, and the most common way to categorize them is by their moisture content:

Dry wagashi (higashi): Less than 20% water content.

Fresh wagashi (namagashi): More than 40% water content.

Semi-fresh wagashi (han-namagashi): Somewhere in between the two.

The most refined type is called jōnamagashi/じょうなまがし, often made with smooth white bean paste and carefully crafted by hand using detailed carving techniques. Once hardened, they’re easier to store and are often used for ceremonial offerings or traditional celebrations.

Ⅲ. Common Misunderstandings

1. Nerikiri ≠ Tang Guozi

Let’s clear this one up — nerikiri is just one style of wagashi made with smooth white bean paste and glutinous rice flour, often molded into seasonal shapes. But today, when people say “Tang Guozi”, they’re usually referring to nerikiri-style confections.

Thanks to historical dramas like A Dream of Splendor, these delicate treats have gained popularity and are often mislabeled as “Tang Guozi,” with some even calling “guozi” a form of intangible heritage. However, the sweets shown in those dramas are more accurately various traditional Chinese pastries, and some media started mixing terms like “Song Guozi” (宋菓子), further blurring the lines.

It’s important to clarify that the nerikiri-style wagashi we often see today are not originally from the Tang Dynasty. The confections that actually made their way to Japan during the Tang era were primarily fried sweets, as fried treats had a longer shelf life and were easier to preserve during travel.

If we’re trying to draw a connection between today’s nerikiri and Tang-era desserts, the more accurate comparison would be with the flour-based sweets that became popular in the Ming and Qing dynasties, when Chinese pastry culture truly flourished. Interestingly, it was around the same time in Japan’s Edo period that the refined form of nerikiri wagashi as we know it was developed. These were later reintroduced to China — and that’s what many people today mistakenly identify as “Tang guozi”.

Another clue comes from Japanese tea culture: Before the Edo period, Japanese tea confections were mostly fruits, mochi (rice cakes), and steamed buns. Nerikiri-style wagashi only became widespread in late Edo, when the price of sugar — a key ingredient in these delicate sweets — finally dropped and made such confections more accessible.

2. Tang Guozi ≠ Sweets from the Tang Dynasty

First of all, the white kidney bean — a key ingredient in nerikiri wagashi — actually originated in the Americas and only spread to Asia after Columbus’s second voyage. It wasn’t until the mid-Edo period in Japan that white kidney bean-based sweets started to be made. Later on, Japanese domestic ingredients and Chinese substitute material came into use.

In Japan, the term “Tang sweets” (唐菓子) has been used to refer to confections that came from China, but this “Tang” is more like how we say “Chinatown” today — it doesn’t specifically mean the Tang Dynasty. The term “Tang” is more like a label used to describe something foreign or imported.

Interestingly, in China, there are currently no national-level intangible cultural heritage listings related specifically to “sweets” or “菓子” in official heritage registries (though local provincial or city records are less clear).

So, if we want to authentically recreate Tang Dynasty desserts, the best approach is to study historical texts and documents. However, the commercially popular sweets we see today — easy to make and visually appealing — are quite far from the true craftsmanship and artistry of traditional Chinese culture.

China has a rich variety of beautiful and delicious “tea snacks,” but these are rarely called “kashi” (菓子). Instead, they go by names like cakes, rolls, pastries, and sticky rice treats.

Ⅳ. Some Historical Evidence

Back to the topic: during the Tang and Song dynasties, tea gradually developed into a standalone commercial beverage, and the snacks served alongside it began to develop their own unique styles. The term “cha guo” (tea snacks) actually originated in the Tang dynasty, marking the early formation of tea-time treats. The famous poet Bai Juyi wrote in his Record of Gratitude for Tea Snacks (谢恩赐茶果等状):

“Today, the esteemed official Du Wenqing respectfully presented tea snacks, preserved pears, and other gifts according to the imperial decree…”

Archaeological finds in China have even uncovered actual “tea snacks” from the Tang Dynasty, providing solid evidence that these were a type of wheat-based food. One such artifact is currently housed in the Xinjiang Museum — and yes, it’s still “resting” there on display. ↑ ↑ ↑

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, tea culture flourished, and snacks became an essential part of the tea-drinking experience. In the Ming Dynasty, teahouses offered a wide range of seasonal and time-specific treats.

A text from the era, Miscellaneous Notes from the Bamboo Islet Studio (《竹屿山房杂部》), lists tea snacks made with wheat flour, rice flour, smartweed flowers, white sugar, and sugar wraps — all primarily intended as accompaniments to tea.

By the Qing Dynasty, this tradition evolved even further. The famed food writer Yuan Mei included many exquisite snack recipes in his culinary collection The Suiyuan Recipes (《随园食单》). One example is Bamboo Leaf Zongzi, made by boiling glutinous rice wrapped in bamboo leaves, forming a small pointed shape like a baby water caltrop.

Another is the Xiao Meiren Snack (萧美人), named after a talented woman outside the south gate of Yizhen city who was known for her delicate creations — buns, cakes, dumplings — all dainty, adorable, and “as white as snow.”.

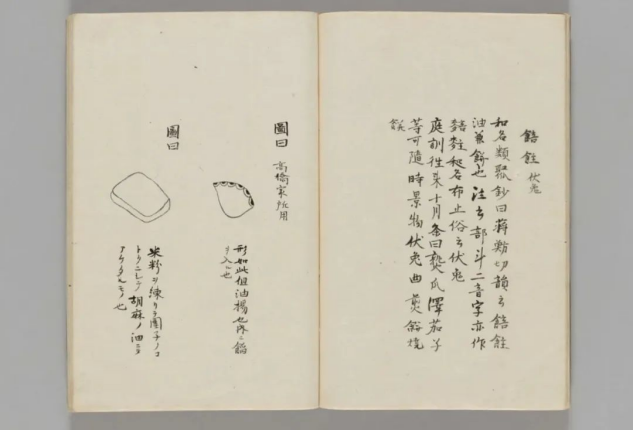

There is a type of dried wagashi called “Rakugan.” According to the Zhu Shi Shunshui Tanqi (《朱氏舜水谈绮》, 1708), the name “Rakugan” is derived from the pronunciation of a snack called “Ruanluogan” in China’s Ming Dynasty.

Additionally, a flower-carving technique used in “Suzhou Ship Pastries,” which was popular during the Ming and Qing dynasties, shares similarities with the Japanese “nerikiri” technique, though it uses glutinous rice rather than white kidney beans as the main ingredient.

Summary

To summarize, can we really say “Wagashi” have no connection to China? After all, the techniques for making pastries, sugar refining, and even pastry carving likely originated in China. That said, it’s undeniable that wagashi have developed unique Japanese cultural characteristics over time.

The Wagashi is broad and does include desserts introduced from China. So claiming an “origins theory” isn’t necessarily deceptive, but it’s absurd to vaguely attribute all kashi to the Tang Dynasty and attempt to claim Chinese Tang Dynasty tea pastry intangible cultural heritage through “nerikiri kashi.”

I’ve even had someone mistake my hanfu for a kimono while walking down the street! That’s why cultural education and awareness are so important. If you’re curious or have thoughts, feel free to share in the comments!

0 Comments