Yang Mi’s Tang-Style Dress Is Truly One of a Kind!

The movie poster for The Litchi Road has just been revealed, and it shows Yang Mi as Zheng Yuting—the devoted first wife who famously declares, “I married him, not the whole of Chang’an.” She’s seen journeying alongside Li Shande, played by Da Peng, giving fans hope that the movie will make up for the regrets left by the drama version.

Eagle-eyed fans noticed a unique detail in her costume: the stripes on her tang dynasty clothing are actually horizontally tie-dyed—a rare design! Interestingly, similar striped prints have recently made appearances on international fashion runways. Were people in the Tang Dynasty really this trendy?

Ⅰ. Inspiration Source

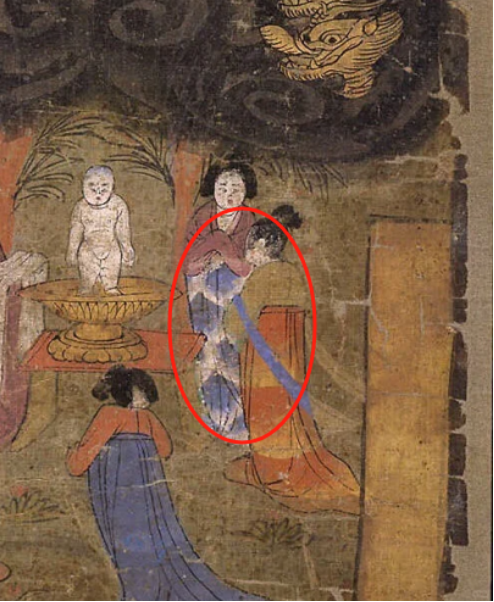

The horizontal gradient skirt draws reference from the hanfu patterns of women in the Tang Dynasty silk painting “The Birth of Buddha“—pretty trendy, right? And these patterns aren’t “printed”—they’re created using Tang Dynasty “Rǎnxié” techniques (染缬 in Chinese), an ancient resist-dyeing craft.

The picture below is from the blog of Little Red Note blogger “槐序梳妆”, who tried to replicate this hanfu. At first glance, this hanfu really has a beauty like fish scale patterns.

The fish-scale skirt design was perfect for flattering the figure and highlighting the beauty of a woman’s curves. Its luxurious yet elegant style also reflected the Tang Dynasty’s cultural taste for sophistication and refinement. As a result, this type of skirt quickly became a fashion favorite and a key symbol of the era’s clothing culture.

Ⅱ. “Rǎnxié” Techniques

Tang Dynasty textiles often featured rǎnxié, or dye-resist techniques, which created beautiful contrast patterns by blocking dye from reaching certain parts of the fabric. Common methods included:

- Tie-dyeing: The fabric is folded or tied with string before dyeing. The bound areas resist the dye, leaving behind soft, organic patterns—similar to modern tie-dye.

- Wax-resist dyeing: Designs are drawn with melted wax, which hardens and blocks dye during the process. After dyeing, the wax is removed to reveal the pattern—this is like the batik technique used by the Bai ethnic group in Yunnan.

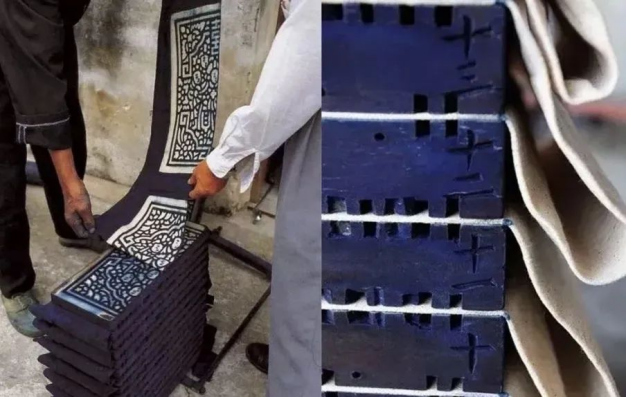

- Clamp-resist dyeing: Intricate wooden blocks with carved patterns are clamped around the fabric. During dyeing, the clamped areas remain untouched, creating striking symmetrical motifs. This method first appeared in the Tang Dynasty and became popular through the Tang and Song periods. The Tang-style Hanfu worn by Yang Mi in the film is a great example of this technique.

Below is an image of a textile artifact created using clamp-resist dyeing.

Dye-resist techniques like rǎnxié served two main purposes: rǎn (dyeing) focused on adding color to fabric, while xié (resisting) focused on creating patterns. These methods are believed to have originated during the Qin and Han dynasties and became especially popular during the Sui, Tang, and Song periods.

Ancient texts offer insight into the practice:

- The Shuowen Jiezi describes xié as cloth used for wrapping.

- The Yunhui dictionary says xié means “to tie and create patterns through repeated dyeing.”

- Xuan Ying’s Yiqiejing yinyi explains that threads are used to bind the cloth; after dyeing and untying, the patterns emerge.

- The Sui Dynasty Record of the Two Principles notes: “Xié appeared during the Qin and Han periods, though its inventor is unknown. By the Chen and Liang dynasties, it was worn by all classes. Emperor Yang of Sui even allowed palace attendants to wear it.”

In short, xié was both a practical and artistic technique, deeply woven into the fabric of ancient Chinese fashion.

Clamp-resist dyeing involves placing fabric between two carved wooden boards with mirrored patterns, then applying dye. This technique was especially common during the Tang and Song dynasties. The pattern on the textile artifact shown above was created using this very method.

Even basic clamp dyeing—simply sandwiching the fabric between flat boards and letting the dye naturally seep in—can create beautiful effects like the two-tone gradient seen on Yang Mi’s Tang-style Chinese dress.

Ⅲ. The Advanced Fish-Scale Skirt

This technique isn’t limited to single-color dyeing. By using gradual pigment blending, artisans could produce soft, watercolor-like transitions. This layering effect adds depth and a 3D feel to the fabric, making the design more dynamic and fashion-forward.

Artifacts from Japan’s Shōsōin treasure house also showcase the versatility of clamp-resist dyeing. The patterns range from repeating motifs to large-scale designs—all depending on the size and detail of the carved boards. The level of craftsmanship is truly breathtaking.

The gradient stripes are impressive, but what’s truly stunning is the layered, fish-scale effect seen on some traditional skirts. If you’ve ever seen one in person, you’d be amazed by the creativity and craftsmanship of the ancients. The natural hues achieved through hand-dyeing simply can’t be replicated by modern industrial methods. In fact, the small imperfections in handmade pieces give them a unique beauty—each clamp-dyed fabric is truly one of a kind.

There’s also the herringbone-patterned skirt. While the herringbone motif dates back to prehistoric pottery, it’s rarely seen as a decorative element on clothing—making its appearance in skirt design especially striking.

Interestingly, similar styles have even popped up on modern fashion runways. Looks like Hanfu has made its way into the fashion world too—love to see it!

Although modern technology has made it easy to produce patterns and fabrics quickly—like through digital printing—it has also taken us further away from the traditional handcraft techniques. True clamp-resist dyeing is now incredibly rare and costly, since handmade work is both time-consuming and increasingly valuable. As a result, it’s uncommon to see authentic “clamp-resist dyeing” products today. Most of the surviving craft has been preserved in places like Wenzhou, Zhejiang, where the technique continues as part of China’s intangible cultural heritage.

Summary

I once came across some clothing made with tie-dye techniques while shopping—some of it even in Hanfu styles. The shop assistant told me that every piece of fabric was a one-of-a-kind work of art, and honestly, I couldn’t agree more.

Thanks to these rich cultural traditions, Hanfu fashion has every right to stand tall and say to the global fashion scene: “The inspiration you’re missing? We’ve had it all along.” Chinese aesthetics continue to capture the hearts of many today.

If you feel the same way, feel free to like, comment, or share—let’s celebrate this timeless beauty together!

0 Comments