What Clothing Brands Are Banned in China?

Have you ever come across news of Chinese consumers boycotting a brand en masse? Why does this kind of thing happen with Chinese people? Sure, one reason might be that Chinese people are pretty unified, but could there be other factors at play?

When a fashion brand gets “banned” in China, it’s rarely just about clothes. It’s about politics, history, and deep-rooted cultural identity. From high-end luxury houses to fast fashion chains, several brands have faced backlash, boycotts, or even removal from online platforms. But what does “being banned” in China actually mean—and how does it relate to the growing movement around traditional Chinese clothing?

Let’s take a closer look.

Ⅰ. What Does “Banned” Actually Mean in China?

It’s not like the legal bans you see in Western countries. Here, a brand can end up “banned” in all sorts of ways:

Their products disappear from big online shops like Taobao or JD.com.

Try searching for them, and you’ll find next to nothing—results get buried or hidden.

Influencers and famous faces rush to distance themselves, cutting off all ties publicly.

State media calls them out, and that’s often enough to spark a nationwide boycott.

Sometimes it starts with the government, but a lot of the time, it’s regular people online who make it blow up. Get people fired up on Weibo, and within hours, it’s a full-blown movement.

Ⅱ. Real Cases: Fashion Brands That Faced Boycotts or Removal

1. H&M: The Xinjiang Cotton Controversy

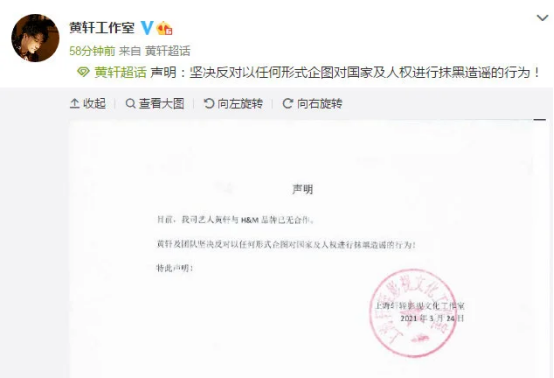

In 2021, H&M issued a statement expressing “concern” over alleged forced labor in Xinjiang and said it would stop sourcing cotton from the region. The response in China was swift and severe. Major platforms like Tmall and JD.com removed H&M listings overnight. On social media, hashtags like #ISupportXinjiangCotton exploded. Celebrities including Huang Xuan and Song Qian immediately terminated their endorsement deals.

People’s Daily, China’s state-run newspaper, called the move hypocritical:

“You can’t eat China’s rice and smash China’s bowl.”

The message was clear: foreign brands entering the Chinese market are expected to respect local sensitivities—both political and cultural.

2. Dolce & Gabbana: Cultural Arrogance Backfires

In 2018, D&G launched an ad campaign featuring a Chinese model struggling to eat pizza and spaghetti with chopsticks. Combined with leaked racist remarks allegedly from one of the founders, the campaign triggered intense backlash. A planned fashion show in Shanghai was canceled, and celebrities like Zhang Ziyi and Chen Kun publicly cut ties.

Chinese media labeled the incident “cultural disrespect disguised as fashion,” and D&G became virtually unwearable in China for years.

3. Dior:“Horse Face Skirt” Controversy (The most influential one in the hanfu community)

While not a local Chinese brand, Dior provides a textbook case of what happens when cultural motifs are mishandled in the Chinese market:

Dior released a pleated skirt that bore a striking resemblance to the traditional Chinese clothing called mamian skirt , a historic Hanfu design dating back to Ming and Qing eras.

The skirt was marketed as part of Dior’s “signature silhouette” and described vaguely as inspired by school uniforms or Korean styles—without acknowledging its Chinese heritage. 🤨

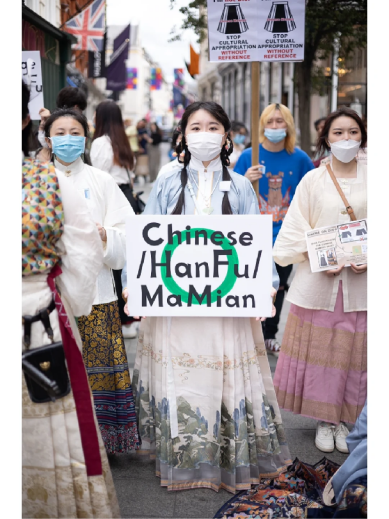

Chinese influencers and Hanfu enthusiasts mobilized online, calling out the brand for cultural disrespect. Protests by Chinese students near Dior’s Paris flagship further amplified the dispute.

As a result, Dior quietly removed the skirt from its mainland China website, disabled comments on its Weibo account, and fueled widespread debate about cultural integrity in fashion.

Industry insiders observed that following the Dior “mamian skirt incident,” LVMH’s revenue in China saw a significant double-digit decline. For Dior specifically, a drop in its beauty segment’s performance in the Chinese market was believed to be partially linked to the controversy.

The incident surrounding the mamian skirt ended up being widely reported by major Chinese media outlets, marking the first time Hanfu—especially the mamian skirt—truly entered mainstream public awareness. Perhaps driven by a renewed sense of cultural identity, many Chinese students abroad began wearing mamian skirts in public, while traditional Chinese clothing enthusiasts back in China also started wearing traditional outfits on the streets. Over time, Hanfu has become much more accepted—people no longer see it as some kind of eccentric costume.

Meanwhile, the mamian skirt gained widespread public attention thanks to the incident. Sales skyrocketed—between March 2023 and February 2024, the online market for mamian skirts reached 2.35 billion yuan (approximately $325 million), marking a staggering year-on-year growth of 503.1%.

Summary

Why Do These “Bans” Matter?In China, fashion is rarely “just fashion.”

Western brands hoping to sell in China must understand these layers. A design or campaign that seems harmless elsewhere can carry unintended meaning in a different cultural context.

China’s fashion “bans” aren’t always official—but they’re real.

While China’s luxury spending keeps rising, major brands keep getting called out for anti-Chinese remarks, discrimination, or treating Chinese shoppers differently. So sometimes, you can’t really blame Chinese consumers for “being too united.” Cultural exchange needs to be built on equality, and Chinese shoppers are really just craving a strong sense of cultural identity.

After reading this blog, do you have anything you’d like to share about traditional Chinese clothing? Feel free to leave your thoughts! 🤗

0 Comments