Is Hanfu Chinese or Korean?

SilkDivas has something to say about this. There was a big debate a while back—around five years ago, over the TV show Royal Feast. Let’s take a look at this blog’s cover art and do a little “guess from the image” challenge.

Which country’s traditional clothing does the cover art depict?

A. China, Tang dynasty attire

B. Korea, hanbok

C. Japan, kimono

D. China, Ming dynasty attire

Let me see who picked “B. Korea, hanbok”—come here and take a gentle scolding! 😤

I. Some previous online controversies

Actually, the left photo shows actor Xu Kai in traditional Ming dynasty clothing with a wide-brimmed hat, taken during the filming of Yu Zheng (director)’s Royal Feast. The right one is a still of actress Wang Churan as a kitchen maid in the show.

Anyway, these photos hit a nerve with Korean netizens. They couldn’t sit tight, claiming it was “stealing Korean clothing.” The director of Royal Feast fired back bluntly: “This is clearly Ming dynasty clothing.” Since then, Korean netizens and the crew have been trading barbs, and the spat has escalated to a national cultural level. Starting with the “hanbok challenge” on Korean social media, they’ve claimed that “Ming dynasty clothing originated from Goryeo styles” and accused Chinese netizens of “twisting historical facts with warped nationalism” for saying “hanbok comes from hanfu.”

Even when Vogue posted a photo of Shiyin in Ming dynasty clothing on its 36 million-follower Instagram account, Korean netizens lashed out, asking why she was wearing hanbok.

II. A little knowledge check

To get back to the point: Hanfu is definitely not hanbok. If we trace their roots, hanbok actually stems from hanfu. It was exquisite clothing gifted to Korea by the Hongwu Emperor, worn only by the nobility.

The reason the two countries’ traditional clothes look so similar goes back to history. Hanbok originated during the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910).

The Ming Shi·Biographies clearly records: “Emperor Chengzu of the Ming Dynasty bestowed a gold seal, imperial decree, coronation robes, nine-emblem regalia, jade tablets, jade pendants, and cloud-patterned shawls upon the Korean royal family. From then on, Korean and Ming dynasty clothing became uniform.”

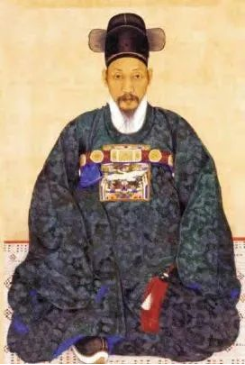

Portraits of Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang of the Ming Dynasty (left) and King Yi Seong-gye of Joseon ↑↑

According to records in Ming Veritable Records, wide-brimmed hats were often given as gifts to neighboring tribes and vassal states.

The Ming court’s repeated grants of official robes to Joseon meant that the court attire of the time bore a strong resemblance to Ming dynasty clothing. Over time, after multiple adaptations, it evolved into today’s hanbok.

We’ve talked about this before. In portraits of late Joseon officials, you can see these changes clearly. While the basic structure of the clothing remained, it lost much of the wide, flowing elegance of earlier Ming-influenced styles and became more restrained and simplified.

You can clearly see that the man’s belt in the picture above sits up near his chest, but the belt in Ming-dynasty hanfu (what Zhu Yuanzhang is wearing) is clearly at the waist—this is indeed the most striking difference.

And that flat-topped hat Koreans are so proud of? Just look at any Ming-dynasty portrait and you’ll see it evolved step by step from our rounded wide-brimmed hats.

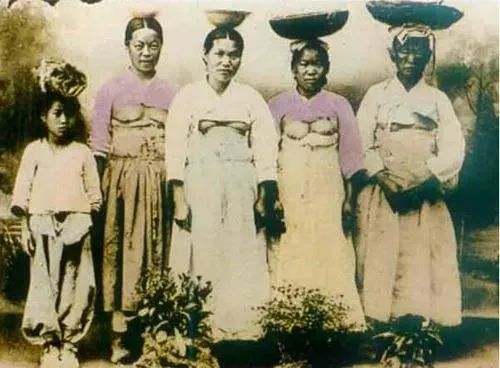

It’s baffling that Korean netizens, whose only traditional “local attire” was the breast-baring style, have the nerve to compare hanbok to hanfu and even claim hanbok is hanfu. It’s as weird as saying a grandson looks like his grandfather. 😂

III. The Deep Meaning of Hanfu

Hanfu, short for the traditional clothing of the Han ethnicity, traces its origins to Leizu, wife of the Yellow Emperor, who pioneered sericulture and garment-making. Its development continued until the Qing Dynasty’s “hair-shaving and clothing reform” policy put an end to its mainstream use.

Evolving over thousands of years, it took on distinct features in different dynasties:

During the Wei and Jin dynasties, influenced by wars and metaphysics, society embraced openness and freedom. Popular styles included long skirts trailing the ground with fluttering ribbons—like the zajuichuijiao (杂裾垂髾, a flowing robe with decorative strips),

The prosperous Tang Dynasty, with its stable economy, vast territory, and open mindset, favored luxurious ruqun (襦裙) and foreign-influenced hufu (胡服, nomadic-style attire), reflecting opulence and cultural inclusivity.

The Song Dynasty, shaped by Neo-Confucianism, leaned toward simplicity. Building on earlier designs, it introduced the beizi (褙子) with overlapping front flaps and buttons centered at the chest.

These garments typically fell below the knees, with cuffed sleeves, edged hems, and narrow lower halves, creating a slender silhouette.

A single hanfu carries really rich symbolism:

The upper garment is cut into 4 panels, representing the four seasons; the lower skirt into 12, corresponding to the 12 months.

Sleeves form a circle when joined, and collars intersect to make a square—symbolizing “heaven is round, earth is square,” with the two embracing in harmony.

The central seam down the back reminds the wearer to always act with integrity and propriety.

China’s traditional clothing embodies the wisdom of our ancestors—their philosophy of life, respect for nature, and reverence for heaven and earth. Can such a heritage really be stolen with a casual claim of “it’s ours”?

Summary

Maybe it’s because our country is so vast and rich in heritage that our ancestors left us too many treasures—so many that we sometimes forget to cherish and carry them forward. But we’re lucky: so many people love Chinese dresses and traditional culture, volunteering to promote them without pay. And it’s good to see these traditions gradually becoming part of daily life.

To those less friendly Korean netizens, a sincere thought: “Time and evidence will tell all.”

0 Comments