Why Was Qing Dynasty Aesthetics “Different” from Other Dynasties?

When we talk about the aesthetics of clothing from different dynasties, there are a few common impressions: the Han dynasty feels solemn, the Tang dynasty magnificent, the Song dynasty refined, and the Ming dynasty dignified. But when it comes to the Qing dynasty, some people online like to joke that, compared to earlier dynasties—especially the elegance of the Song period—the Qing dynasty clothing can come across as a little “tacky.” Do you agree?

At Silkdivas, we believe that aesthetics aren’t about being superior or inferior. There’s no such thing as “better” or “worse” taste. But what we can do is look at the technical and stylistic differences between Qing clothing and the hanfu dress traditions of earlier dynasties. (This article simply explores the contrasts in aesthetic style across history—it’s not meant to criticize or belittle anyone, so please don’t take it personally~)

Ⅰ. Strong Craftsmanship, Weaker Cultural Depth

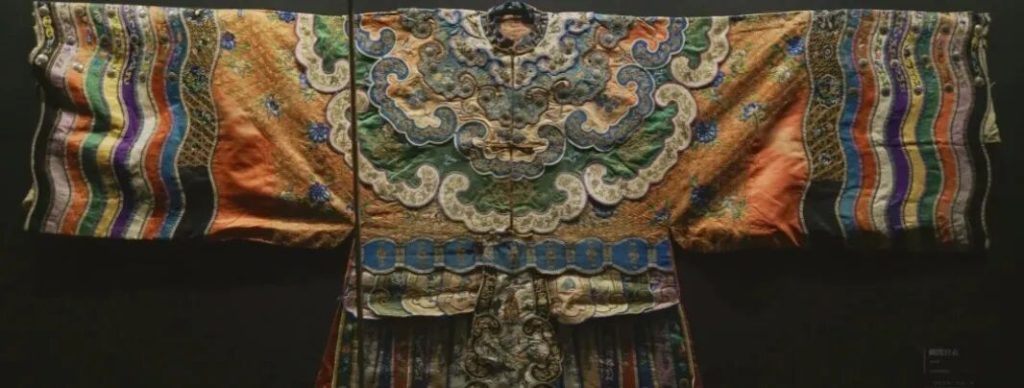

The Qing dynasty inherited and perfected many technical skills from earlier dynasties. If you look closely, the embroidery is incredibly dense, the stitching remarkably fine—clearly, the craftsmanship was top-tier. But when the techniques advanced faster than the aesthetics, what happened?

The result was often excess. Think of it like a beginner in painting: eager to try everything at once, they crowd the canvas with flowers, birds, buildings, geometric patterns—abstract here, realistic there. Many Qing garments ended up looking like patchworks of copied and pasted motifs, impressive in skill but sometimes lacking cohesion.

For many global Hanfu enthusiasts, Mongolia is at least a familiar name—once the largest empire in the world, yet still largely assimilated into Chinese culture.

The Jurchens, the ancestors of the Qing rulers, came from a nomadic background. Before their rise, their level of cultural development was not as advanced as that of the Han, and much of their refinement came from learning and adopting Han traditions.

To put it simply, the aesthetics of Qing dynasty clothing can be compared to that of a newly rich family. Imagine someone who suddenly strikes it rich, buys a huge house, and then fills it with every possible style of décor—European, American, Italian—all at once. The craftsmanship is undoubtedly impressive, but the result feels flashy and incoherent.

In contrast, hanfu dress aesthetics are more like “old money.” (this is my personal opinion and does not represent the views of all Chinese people.) The wealth might be the same, but the cultural depth runs much deeper. After all, Hanfu evolved over nearly 3,000 years, while Qing dynasty dress only developed for about 268 years—a huge gap in heritage and refinement.

This is why Qing embroidery often feels like it “spared no expense”—the colors are highly saturated, almost as if dye was limitless. At first glance it dazzles, but after a while, the overwhelming details—wave patterns, multiple borders, densely packed motifs—can be visually exhausting, even unsettling.

Put bluntly, maximalists might love this style, but for most Chinese people, it clashes with a traditional sense of beauty. Chinese art, like landscape painting, values restraint and empty space. The principle is closer to “less is more,” a philosophy that shapes not only aesthetics but also a broader cultural way of life.

Ⅱ. Some Examples

Early Qing fashion was fairly understated (left side), but by the late Qing period (right side)—much like how “extravagant fashion excesses” emerged in the final years of other dynasties—the Qing took it a step further: an outright eccentric, almost uncanny aesthetic that reached extremes. It was overly flashy, densely ornamented, and bordering on surreal.

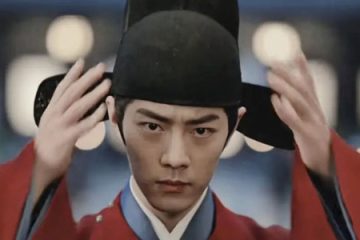

That’s why zombies in Chinese films often wear late Qing official robes. The somber dark indigo fabric, paired with a splash of red on the hat top, looks eerie no matter how you see it. (If you’re curious about this, click here to learn why zombie movies favor Qing official attire.)

Compare that to the vibrant, multicolored official robes of the Tang, Song, and Ming dynasties, and the Qing version really feels like “going to court is like going to a funeral.” Late Qing color palettes specialized in vivid, intricate embroidery set against dull, muted backgrounds—creating a sensory experience that felt almost otherworldly.

By contrast, the highest form of aesthetic in Chinese culture has always leaned toward simplicity and natural elegance. Think of Song dynasty style: the colors might not be bright, but they radiate a quiet grace that calms the heart. With just a few subtle tones, you get a refined visual harmony.

This kind of beauty doesn’t overwhelm you at first sight—it grows on you, becoming more pleasing the longer you look. That is the essence of the traditional Chinese love for understated elegance.

Summary

When someone lacks something, they tend to crave it more—and dynasties are no exception. The Qing dynasty clothing had its own energy and splendor, but it didn’t necessarily resonate with most Chinese people.

That said, taste is highly subjective, and everyone sees beauty differently. In today’s world, people embrace a wide variety of aesthetics, and that’s perfectly normal—after all, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. What do you think?

0 Comments